● Consumers. That's right, you and me, the people who want access to health care. We demand more and more resources be devoted to saving ourselves and our loved ones, even when the chances of success are slim. We think of health care differently than we think about any other resource that exists in finite supply simply because someone else--the payers indicted below--is paying for it. So we tend to use more than we would if we had to open our own wallets any time we sought care. In the aggregate, that decoupling of demand from willingness or ability to pay will likely drive costs upward. This is the source of suggestions we've explored in the past that we pursue reforms aimed at making people think about how care is paid for and put some skin in the game. But are we the villain or merely the dunces unwittingly aiding the real villain?

● Medical suppliers. The folks selling providers the equipment they need to do medicine in the 21st century. Are they marking up prices on their products ever higher, forcing costs up across the entire system?

● Payers. The classic mustache-twirling movie villains. They gladly take our health care dollars--paid through monthly insurance premiums--and skim their cut off the top. They restrict access through the underwriting process we've discussed before. And they're the most visible culprit in the soaring cost saga, as they're the ones constantly raising the rates on their insurance policies. But is it too obvious? Are they being set in a classic case of misdirection from a more guilty party?

● Providers. Hidden beneath the veneer of benevolence, could a cold and calculating killer lurk? Providers are the actual purveyors of care in our system. They're the doctors and hospitals who deliver the care that consumers seek and for which payers cut the check. They're the consummate good guys, the Bones McCoys and the Princeton-Plainsboros that give us lifesavers like the irascible but brilliant Dr. House. They're the ones we trust, the ones politicians assure us won't be separated from us by some bureaucracy. But if I know anything about whodunnits (or story arcs in 24), often it's the one we trust most who turns out to be the most likely culprit.

Let's begin our investigation with a look at a table prepared by the good folks at the Kaiser Family Foundation comparing popular opinion on certain features of health care with expert opinions:

This certainly seems to be indictment of the consumer. A cavalier attitude about actually getting quality for every health care dollar spent, and obstinacy in sticking with instinct over evidence. But even with our apparently complicity in the crime, that table hints at larger structural issues in our current system that extend beyond even the consumers driving it.

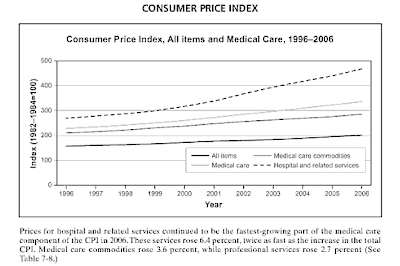

How about medical suppliers? Are they driving the cost increases by charging more and more, forcing providers to raise their prices and, ultimately, insurance companies to raise premiums to cover the bills from providers? The Consumer Price Index used to measure inflation contains a number of medical items, including a "Medical care commodities" component that includes drugs, equipment, and supplies. The 2008 Handbook of U.S. Labor Statistics has the following graphic comparing growth rates in different medical components:

Over the decade they looked at (1996-2006), the prices of those medical commodities rose but not nearly as fast as the "Hospital and related services" component of the CPI. Perhaps vendors' prices are being pulled up by the rising costs in hospitals, not driving them. Let's look at one more suspect--payers--before we turn our attention to providers.

Payers are insurance companies (most are private but public payers, i.e. Medicare and Medicaid, do exist). Over the past year or so the newspapers have been replete with stories of insurers raising their prices. Stories like this one from California earlier this year:

Anthem Blue Cross recently informed many of its approximately 800,000 individual policyholders that premiums would increase by as much as 39% on March 1. Anthem also informed members that it might start adjusting premiums more often than once a year.

Or this one from Maine, resolved only last month:

A Maine judge upheld a state regulator's rejection of an insurer's premium-rate hike, which would have raised the cost of plans purchased by individuals by 18.1 percent compared with the previous year. [...]

Earlier in the year, Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield got permission from Maine regulators for a 10.9 percent increase, so the court battle was really over an additional 7.2-percentage-point proposal.

Or the standoff last month in Massachusetts, in which insurers briefly stopped issuing new policies in response to state regulators rejecting their proposed premium hikes:

The standoff between Massachusetts regulators and health insurance companies intensified yesterday, as most insurers stopped offering new coverage to small businesses and individuals, and state officials demanded that the insurers post updated rates online and resume offering policies by Friday. [...]

Health insurers, however, said they could not calculate new rates until a judge rules on their request for an injunction to prevent the state from continuing to block increases for the coverage period that started April 1. Insurance carriers had proposed premium rate increases averaging 8 to 32 percent, which the state found excessive.

Note that around 30 states require health insurers to justify premium increases; in those states, only if the state insurance regulators sign off on the increases can they go forth. That's why in Massachusetts the government could simply say no to proposed hikes and in Maine the insurance commissioner could allow a smaller hike than desired by BCBS.

These kinds of abrupt rate hikes (or attempts at rate hikes) make it easy to demonize insurers and at least ostensibly finger them as the cost-raisers. But is there a deeper reason behind the premium increases? Let's look at the final suspect before we draw any conclusions.

Providers, as mentioned above, are the hospitals and doctors who actually provide health care in our system. But as we saw in the CPI data mentioned earlier, hospital costs have risen faster than other costs in the health care system.

In February, Health Affairs published a fascinating paper (now behind a paywall, unfortunately) entitled "Unchecked Provider Clout In California Foreshadows Challenges To Health Reform". In it, the authors examine the dynamic between insurers and providers in California (though I'd submit that California is a microcosm of nationwide problems, its issues a decent analog of those faced by many other states). In case you don't know, the way prices are set in our system is a bit like a peacock mating ritual: there's a lot of dancing, a lot of mesmerizing plumage, a good show, but in the end somebody is getting fucked.

A payer and provider sit down at a negotiating table and figure out how much the payer is going to reimburse the provider for various services. But as that Health Affairs paper describes in detail, the scales are often tipped in favor of providers in such negotiations, an idea we touched on long ago in (Anti-)Trust Me. The paper points to an odd feature of the way this process shakes out:

As the dominant payer for the elderly and disabled, Medicare sets prices and is generally indifferent to providers’ negotiating clout. Private payers, which must negotiate with all hospitals and large physician practices, generally agree to pay much higher rates than Medicare pays to persuade providers to enter into a contract with them.

If accountable care organizations lead to more integrated provider groups that are able to exert market power in negotiations—both by encouraging providers to join organizations and by expanding the proportion of patients for whom provider groups can negotiate rates—private insurers could wind up paying more, even if care is delivered more efficiently.

This is a fascinating--if paradoxical--point. Care that's delivered more efficiently is often, by its very nature, more consolidated care. But in that case, more efficient and ultimately less expensive (to the provider) care can actually cost payers and patients more money because providers in such situations have more clout and can negotiate higher reimbursement rates. The paper pointed to other perversities in the system:

One commonly cited factor in the shift to broad provider networks was consumers’ desire for broad provider choice, even in HMO products, following the managed care backlash of the mid-to-late 1990s. For example, a Fresno benefit manager’s analysis found that physician overlap in two prominent health plan networks was 97–98 percent. This reality weakens the position of health plans. If plans cannot exclude providers from their network because of customers’ demands for broad networks, they cannot credibly threaten network exclusion. That fact undermines their ability to resist providers’ demands for higher payment rates.

People want to be able to choose their doctor or hospital but what that means is that insurance plans often have to include almost every provider in an area. So at the negotiating table, providers (especially well-known or "must-have" facilities) know that the insurer can't credibly say no and walk away, swinging the balance of power in the negotiation to the provider. And, in California at least, it appears they're not shy about using that power:

Between September 2008 and October 2009, California hospitals charged health insurers an average of 53% more than the amount they reported that it cost them to provide services to insured patients, according to a Sacramento Bee investigation.

The gist of the Health Affairs paper, as you probably gathered, is that providers use their leverage to squeeze more money out of insurers, negotiating ever-higher reimbursement rates. The exception, as noted in one of the above quotes, is the public payer, Medicare. Medicare doesn't negotiate with

The independent Medicare Payment Advisory Commission that's charged with advising Congress on Medicare-related issues pushed back on this accusation in its last report to Congress on Medicare payment policy:

Why are profit margins on privately insured patients so high? Is it because hospitals under financial stress tend to have significant Medicare losses, which force them to have relatively high private-payer prices? The answer is no. We find instead that hospitals under financial pressure tend to control their costs, which makes it more likely that they profit from Medicare patients. In fact, we find that Medicare margins are lowest in the hospitals with abundant resources (i.e., low financial pressure). Therefore, it appears that hospitals are raising prices when they have the market power to do so. As revenue rises, costs rise, and Medicare margins fall. Our key findings are:

- Costs vary widely from hospital to hospital.

- An abundance of financial resources is associated with higher costs.

- Higher costs cause losses on Medicare patients.

- As a result, hospitals with abundant financial resources tend to have Medicare losses.

- In contrast, hospitals with limited financial resources constrain their costs. Medicare payments are usually adequate to cover the costs of these financially pressured hospitals.

The Commission has argued that high profits from non-Medicare sources permit hospitals to spend more, and nonprofit hospitals tend to do so (for-profit hospitals may retain a larger share of their revenues as profits). The causal chain is as follows: A hospital’s market power relative to insurers, payer mix, and donations determines its level of financial resources. When financial resources are abundant, nonprofit hospitals spend more, add employees, and increase their costs per unit of service. High costs by definition lead to lower Medicare margins because costs do not affect Medicare revenues (which are based on predetermined payment rates). Therefore, when costs increase, Medicare margins ((revenue – costs)/revenue) decrease. In other words, income affects spending and costs per unit of service. Hence, if Medicare were to increase its payment rates, hospitals might spend some or all of that revenue rather than use it to lower the prices charged to private insurers. [. . .]

The data indicate that the hospitals with the largest Medicare losses tend to be in better financial shape than other hospitals. From 2002 to 2006, hospitals with low Medicare margins had median total (all payer) margins of 4.6 percent compared with 3.4 percent for hospitals with high Medicare margins. In addition, net worth for the high-cost hospitals rose by 17 percent from 2004 to 2006 compared with a 14 percent rise for low-cost hospitals. While causation may flow in both directions to a degree, the data suggest that the primary reason Medicare margins are inversely related to private-payer profits is that high non-Medicare profits are followed by high hospital costs.

It may appear odd that hospitals with high costs have high total profit margins. In a typical industry, high profits are not associated with high unit costs. The hospital industry is different, however, because of the dominance of nonprofit providers, the influence of payer mix, hospital and insurer market power, and the effect of investments and donations on hospital finances.

Increasing Medicare payments is not a long-term solution to the problem of rising private insurance premiums and rising health care costs. In the end, affordable health care will require incentives for health care providers to reduce their rates of cost growth and volume growth.

A long quote to include here (with all emphasis in it mine), to be sure, but jaw-droppingly brilliant in its simplicity and frankness. MedPAC's point is that the hospitals that suffer losses from Medicare's (relatively) low reimbursement rates are those that are already swimming in money from other sources. Providers that are somewhat cash-strapped ("under financial pressure") are forced to operate more efficiently and consequently they actually turn a profit on Medicare patients. Providers that make more want to spend more. This is a notion we'll return to below when we consider regional variations in diagnosis frequency.

But do we have any other evidence, aside from MedPAC's allegations and the evidence of providers using their clout to drive up prices in California? Is this happening in other states? Actually, yes. In January, the Massachusetts AG (Martha Coakley, best known as the horrible campaigner who allowed Scott Brown to beat her in the race for Ted Kennedy's Senate seat) released a report arguing essentially the same thing that Health Affairs article did a month later:

Massachusetts insurance companies pay some hospitals and doctors twice as much money as others for essentially the same patient care, according to a preliminary report by Attorney General Martha Coakley. It points to the market clout of the best-paid providers as a main driver of the state’s spiraling health care costs.

The yearlong investigation, set to be released today, found no evidence that the higher pay was a reward for better quality work or for treating sicker patients. In fact, eight of the 10 best-paid hospitals in one insurer’s network were community hospitals, which tend to have less complicated cases than teaching hospitals and do not bear the extra cost of training future physicians.

Coakley’s staff found that payments were most closely tied to market leverage, with the largest hospitals and physician groups, those with brand-name recognition, and those that are geographically isolated able to demand the most money.

Consider the case of Maryland. Maryland gets around the issue of provider clout driving up prices by removing the insurer-provider negotiation from the process for acute-care hospitals. That is, they set reimbursement rates:

In Maryland, an independent agency has been setting rates since 1977 for all patients, including Medicare beneficiaries, at the state's acute-care hospitals.

In establishing the Maryland Health Services Cost Review Commission, the state Legislature wanted a way to set reasonable prices while also generating enough money to cover patients who couldn't pay their bills. The system has helped bring Maryland's hospital costs below the national average.

But the state's hospitals have been required to turn over to the state data covering everything from a patient's diagnosis, demographic information and treatments to how much the patient was billed, which are made public. [...]

The state commission has about 30 people on staff to come up with the rates for the state's 47 acute-care hospitals. It also sets rates for privately insured patients at the state's specialty hospitals. The rates take into account each hospital's wages, charity care and severity of patient illnesses.

The commission, for example, requires St. Joseph Medical Center in suburban Towson, part of Denver-based nonprofit Catholic Health Initiatives, to charge $984 for an overnight stay, and Johns Hopkins, $1,555. For a basic chest X-ray, St. Joseph's rate is $81 and Hopkins's rate is $155. The differences reflect Hopkins's higher costs as a teaching hospital and its care for generally sicker patients.

Private insurers aren't allowed to bargain for discounts on hospital payment rates, though patients may not notice the difference. But that isn't the case for the uninsured. In other states, hospitals typically charge the uninsured steep prices that no insurer actually pays, forcing the hospitals to write off the charges they can't collect payment for. In Maryland, where hospitals know they will get reimbursed for charity care, hospitals charge the same rate whether a patient has insurance or not.

The system has largely reined in hospital costs. In 1976, Maryland hospital costs were 25% more per case than the national average; by 2007, the latest year for which data are available, Maryland's costs were 2% less than the national average. Maryland also saw the nation's second-slowest increase in hospital costs during the same period, said Robert Murray, the commission's executive director.

On average, Maryland hospitals charged patients 20% above the cost to treat them in 2007, compared with a national average of 182%, according to the American Hospital Association.

In picture form:

But keeping providers from inflating reimbursements is only half the battle. Medicare and certain segments of the Maryland market may be able to keep providers in check on that front, but providers in those situations can still over-diagnose, even if they can't overcharge:

A recent paper in the New England Journal of Medicine does find that there is significant regional variation in how patients are diagnosed. Simply examining regional variation in diagnoses may simply indicate that one region has more sick people than another. To get around this problem, the authors examine what happens when Medicare beneficiaries move. As people age, they are more likely to become sicker and thus accumulate more diagnoses. However, individuals who moved to high cost regions were more likely to acquire more and more serious diagnoses than those who moved to lower cost regions.

To determine diagnose severity, the authors used Hierarchical Condition Categories (HCCs)–which Medicare uses as a risk adjustment mechanism to reimburse Medicare Advantage managed care plans–to create a risk score. Ranking individuals by risk score quintile, this chart clearly shows a trend that when individuals move to higher cost regions, they are more likely to accumulate more diagnoses and increase their HCC risk score.

Take a moment to let that sink in. Medicare patients who move to one of the high-cost regions of the country become more likely to be diagnosed with something. The implication here seems to be that we have a bit of vicious cycle going on: providers who can make more on their work tend to make more work (i.e. diagnose more illnesses).

J'accuse!

On the basis of this evidence, Inspector Stanek constructs an admittedly oversimplified narrative that goes something like this:

We have in place a health care system that's sick in many ways. Consumers are shielded from much of the cost of the care they consume and consequently aren't overly concerned about the quality bang they get for their buck or how well money is being spent; we want it all but don't really want to see our premiums go up or our choices of providers limited. Meanwhile, private payers lack the will and the clout to stand up to providers (the robust public option component of reform was supposed to give them the incentive and the cover to do this but it didn't survive the Senate). They accept the ever-rising prices hospitals assign to their services, dutifully passing the costs on to consumers in the form of premium hikes. In states where regulators are empowered to challenge these hikes, insurers cry foul and decry government interventions that threaten their solvency. Unfortunately for them, nobody likes insurers in the first place, which doesn't help their case when they're caught holding the bag for provider avarice. Meanwhile, medical suppliers latch onto the gravy train, knowing that providers--with their deep pockets--can afford a bit more for the supplies that keep their businesses running. Even so, as we saw in the CPI data above, the costs of medical supplies are rising much slower than are hospital costs.

All the suspects have a hand in the crime but one in particular is relentless and increasingly audacious in its bludgeoning of affordability.

Providers in the conservatory with the candlestick.