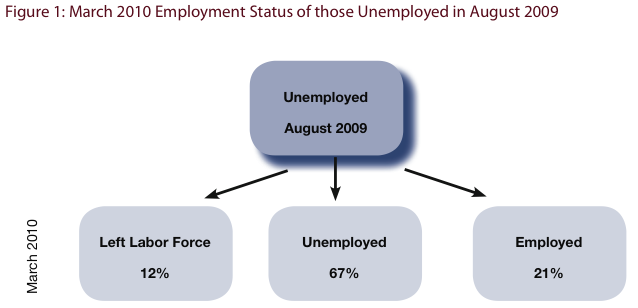

The specter of an extended period of abnormally high joblessness has been hovering over this economic recovery for months now. We're no longer in a recession (GDP has been growing for three straight quarters, and presumably GDP is also growing in the quarter that will conclude at the end of this month), yet, despite an occasional encouraging sign, unemployment remains persistently high. And not just in the sense of a great many people being unemployed in any given month; the ranks of the long-term unemployed (technically, people who are out of work for 12 months or more) don't seem to be thinning. We're reminded of this every month when Congress votes to extend unemployment insurance to people for whom it should've long ago expired. Take it look at this disheartening poll from Rutgers showing what had happened by March of this year to people who were out of work last August:

When I saw that graphic comparing unemployment rates across education levels, I was reminded of an idea first introduced four decades ago by Michael Piore: the notion of the dual labor market. You can read about it in 3-ish short pages in "The Dual Labor Market: Theory and Implications" (incidentally my copy of the Grusky reader somehow disappeared a while ago--I'm still pissed about that). At the risk of oversimplifying, Piore essentially breaks up the labor market into "good jobs" (the primary market) and "bad jobs" (the secondary sector):

One sector of the market, which I have termed elsewhere the primary market, offers jobs which possess several of the following traits: high wages, good working conditions, employment stability and job security, equity and due process in the administration of work rules, and chances for advancement. The secondary sector has job that are decidedly less attractive, compared with those in the primary sector. They tend to involve low wages, poor working conditions, considerable variability in employment, harsh and often arbitrary discipline, and little opportunity to advance.

An extra degree of gradation is added by the inclusion of an intermediary labor market (jobs somewhere between the really good and the really bad) but it's still a picture of the labor market that easily could have been taken by Ansel Adams. In part, the dual labor market model is a theory of poverty, as indicated in that linked piece where Piore points out that "The poor are confined to the secondary labor market. Eliminating poverty requires that they gain access to primary employment." More broadly, it's a powerful account of inequality and stratification in employment. Moreover, it makes sense intuitively and experientially.

Since the less-educated are much more likely to end up in the secondary sector than in the primary market, the graph up top seems to be indicating that the recession is falling especially heavily on the secondary sector, which you can see from the graph isn't historically all that unusual. College graduates, on the other hand, always seem to have the best prospects. Even now, when the unemployment rate for college grads is higher than at any time on that graph (i.e. since 1992), it's still only around 5%. Of course, that graph only measures U3 unemployment so it doesn't account for people who get discouraged and drop out of the labor force or are doing part-time work or are otherwise underemployed. But the reality remains that people groomed for the primary market tend to weather the economic storm much better than those confined to the secondary market.

But with warnings of prolonged joblessness and an emerging consensus that this recovery isn't going to look like the recoveries we're used to, one has to wonder how returning jobs are going to be stratified. Is the blue line in that graph--people with less than a high-school education, prime suspects for secondary sector participation--going to plateau while the others gradually come down? Or will all four lines slowly sink together? Call me pessimistic but it doesn't seem all that likely to me that a rising tide will lift all boats here; it seems likely that the tide will be a little more discerning. And that's probably not good news for people in the secondary market.

In fairness, there is one more level of stratification--within college grads--that's worth pointing out. Despite "glimmers of hope" for new college grads this year, recent graduates are not faring as well as older or more experienced college grads:

Thomas J. Nardone, an assistant commissioner of the Bureau of Labor Statistics, said that the jobless rate for college graduates under age 25 was 8 percent in April, up from 6.8 percent in April 2009 and 3.7 percent in April 2007, before the recession began.

So things certainly aren't as bright for our cohort of college grads as they are for college grads in general. But the prospects are still much better for young 20-something degree-holders than they are for captives of the secondary market.

No comments:

Post a Comment