My views here are, I think, relatively non-ideological and lean toward empiricism. Bu I have some built-in biases, though I would argue that there are logical/empirical roots to these preferences.

My major guiding axioms here are the following:

- If well-functioning markets are possible, they are preferable to the alternative.

- If people are capable and equipped to make them responsibly, choices/options are good.

- Corollary: This is true even if choice is largely an illusion.

- A policy that can be passed and implemented is superior to one that cannot.

- Corollary: Smaller changes are generally preferable to larger ones, and larger changes arrived at through evolution are generally preferable to those arrived at through discontinuous, disruptive change.

- Spock's Dictum: The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few. Or the one.

(What a fucking gut-wrenching death. Part of why TWOK comes in #1 in my ranking of Trek movies).

So this is my starting point. A healthy respect for the benefits of market dynamics, coupled with a systems-oriented perspective that doesn't unduly privilege the individual to the detriment of the overall system. Perhaps that means we're starting with an intrinsic paradox or contraction but here we are.

So here's what would make me embrace single-payer over the (ACA-compliant) status quo.

Occam's razor

I consider the new exchanges (marketplaces) under the ACA a grand experiment. Not just in policy but, deeper than that, in human behavior. They're the first large-scale, widespread chance for individuals to shop for commercial health insurance in a coherent marketplace. Previously nearly everyone had their insurance choices dictated either by their employer's HR department or the vicissitudes of the chaotic, disorganized individual market that used to exist for everyone else. How people respond to this experiment is the single most important factor in my thoughts on single-payer.

We know people aren't perfectly rational calculators, they're boundedly rational beings with limited time, resources, and cognitive bandwidth. And that's why the most important function of the exchanges (after disbursing federal tax credits, SCOTUS willing) is to organize the market. Grouping plans by relative generosity into actuarial tiers identified by metal designations, bronze to platinum, allows people to easily make apples-to-apples comparisons.

Eliminating individual rating beyond the most basic of factors--family size, geography, age, and tobacco use--means that the sticker price of a health insurance plan is in fact its price. That means competing plans can legitimately and meaningfully be lined up next to each other for comparison on a website, something never true before. Premiums and deductibles are right there for inspection by the consumer, no strings attached.

This year the federal exchange, healthcare.gov, added a feature that allows shoppers to narrow or sort plans by "medical management program." Consumers now can quickly see which plans offer special programs to support enrollees with a variety of conditions, from asthma to heart disease to depression to high blood pressure.

Plan quality and participating providers are additional dimensions of interest to shoppers that exchanges will get better at displaying for easy comparison as time goes on.

The point of all this being that exchanges narrow down the decision-making process for health insurance by boiling it down to a few key factors and allowing shoppers to easily compare plans along those dimensions. By providing that structure, they allow consumers to make meaningful decisions and to send clear signals to insurers selling in the marketplace. The design of exchanges not only acknowledges bounded rationality, it harnesses it to salvage market dynamics.

But a critical assumption here is that this simplified choice architecture (an idea I've explored with delight before in "Order Out of Chaos") is enough to empower consumers to be savvy shoppers. If that's not true, the entire edifice begins to crumble. We heard it last year in scattered anecdotes that provide precious little context to determine if the problem is widespread or localized. Some people bought a plan not understanding their cost-sharing responsibilities, ending up with higher deductibles than they wanted to pay. Others bought plans without scrutinizing the provider director and found desired doctors weren't included (cases where insurer provider directories were simply wrong, primarily in California as far as I can tell, are different--that's simply fraud or negligence and ought to be pursued by local authorities).

Those stories are all examples of people buying coverage they didn't understand and thus ending up with plans that didn't accurately reflect their preferences. If the average consumer cannot properly evaluate their risk, judge when to seek "necessary" care, or make appropriate choices that correspond to their preferences then the marketplaces will fail. Like all ideas based on markets, exchanges are predicated on the assumption that people are equipped and able to make the best decisions for themselves. If most people end up with coverage they didn't want (e.g., because their preferred doctor or hospital isn't in-network for the plan they chose or because they didn't understand the financial commitment entailed by taking on a large deductible), then we have a problem. If people can't effectively translate what they want into what they buy, the markets won't work. The marketplaces are supposed to be the mechanism by which consumers translate their preferences into purchases and thus send clear signals to sellers. If the consumer turns out to be the weakest link here, then markets aren't the answer.

Now we need to be careful here. Anecdotes are not data and Gallup polling from last November suggests most people who bought exchange coverage are happy with it. And the new marketplaces established under the ACA remain a vanishingly small component of the total insurance market, primarily catering at present to people who are the most likely to be unfamiliar with health insurance concepts and design. There will be a learning curve. But it's entirely possible that most people in employer coverage, unaccustomed to comparison shopping for insurance in the open market, are not particularly well-equipped to buy their own insurance either. And those who hope that down the road the exchanges become a platform for the future of health insurance selection (well beyond the ~10-20 million people expected to gain coverage through a public exchange in the next few years) may yet have to grapple with that reality.

So that's the primary (empirical) thing that will turn me to single-payer. If people prove unable to competently shop for a health insurance plan that matches their preferences, then there's no reason to have competitive insurance markets. Indeed, a more paternalistic system would be demanded by such a situation. And maybe I need to surrender my moderate liberal/center left card to say so, but I really hope that's not the case.

But if we need a paternalistic system, an Occam's razor to further simplify the options available to people (to none, I suppose, since they'll get a standardized policy with likely no cost-sharing and all-providers in the U.S. in-network), then single-payer is the answer.

E Pluribus Pluribus

I argued in the previous post ("E pluribus unum") that single-payer isn't necessary if we can achieve its primary goals by aligning multiple payers toward similar ends. If we want providers to adopt a new health care delivery model that requires a different payment model to sustain it, then all payer-boats need to start rowing in the same direction to enable those providers to make that change. All health care is local and that sort of alignment needs to happen at the local/state level, though arguably such a major payer as Medicare needs to be onboard if those local changes are to succeed. And the federal government is furiously providing seed money to the states to make those local changes.

But if multi-payer alignment fails to achieve those goals then it's not going to be enough. And by failure I mean that either these coalitions fray and disintegrate, or they're simply too weak to enable or push the change they seek on the provider end. There are a lot of moving parts here and there's no guarantee that the current push to get competing payers on the same page will succeed. Payers need to maintain enough differentiation to try and best their competitors in the marketplace. Is this kind of homogenized differentiation sustainable?

I said in the previous post that a a primary argument for single-payer is that it provides unified policy direction across the health system. If that unified direction can't be achieved in a multi-payer environment then single-payer may well be the only hope we have to fix our broken payment and delivery system. This, again, is a prospect I don't relish.

Prices!

There's plenty of reason to believe that much of what's wrong with health care costs in America isn't just traced to our woefully inefficient delivery system but to our prices (see: "It’s The Prices, Stupid: Why The United States Is So Different From Other Countries" and "21 graphs that show America’s health-care prices are ludicrous").

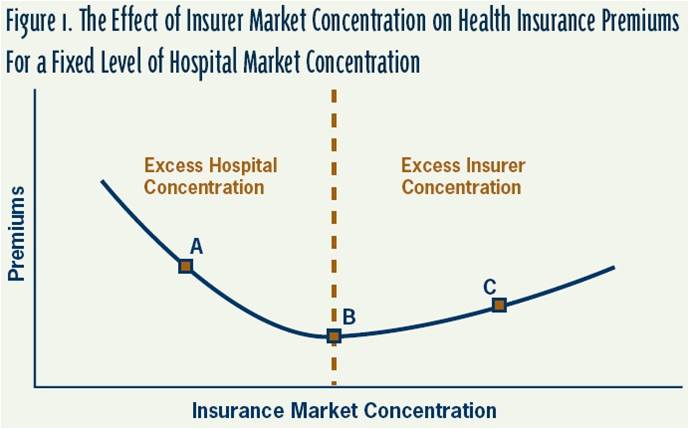

If we don't find a way to tackle high prices on the health care provider side (a departure from this talk of health care insurance market dynamics) then we're sunk anyway. In fact, there's some reason to believe a competitive insurance market could be counterproductive:

(h/t to the Incidental Economist)

What the graph says is that if a single insurer dominates a market, they'll jack up premiums and consumers will be hurt (a great argument for competitive insurance marketplaces!). But if a consolidated health care provider organization dominates the market, a fragmented insurance marketplace may just make it easier for them to extort ever higher prices for health care services (see my now classic in the field "The Case Against Providers") by weakening the bargaining position of any individual health insurance company. In other words, insurer competition is good...to a point. And that point is where insurance market fragmentation benefits health care providers at the negotiation table. What a tenuous balance!

Ultimately if insurer competition means that hospital systems (which are quickly buying up physician practices, as well) can demand higher prices because insurers are poorly positioned to say no, then we all suffer. Which would suggest we need a single payer with the monopsony power to simply dictate reimbursement rates to provider systems.

Again, I don't believe that's ideal but if competitive insurance markets turn against the consumer in this fashion (after all, higher provider reimbursements directly translate into higher insurance premiums) then decisive action is needed. Time will tell!

Requiem for a Dream

I want markets to work. Long-time readers (j/k, I know there are none) will know that five years ago I was a huge, huge, advocate of having a robust public option in the new exchanges. On the assumption that an insurer paying (at least initially) Medicare +5% rates would put tremendous pressure on health care providers to capitulate to lower rate/price demands of newly-en-balled commercials demanding more reasonable rates to avoid consumer defections to a cheaper public option. The value of the public option to me was not that people would enroll in it, but rather that its mere existence would re-shape the provider-commercial insurer relationship to ensure that contracted rates came back to earth so that commercial insurers could reasonably compete with a public option empowered to dictate its own rates.

I have been pleasantly surprised to find that the public option seemingly wasn't necessary. Private insurers selling in the exchanges have been going crazy with cost containment. PwC found that exchange premiums were 4-20% (!) cheaper than employer-based plans of equivalent generosity. McKinsey found that narrow provider networks of the sort gaining popularity in the exchanges could lower insurance premiums by as much as 26% (!) with no appreciable difference in quality of care.

The reality is that in a world where health insurers can't find savings by shedding risk (read: dumping or avoiding sick people) they have to keep premiums down through a few strategies, including: 1) smarter benefit design, nudging shoppers toward higher-value services and providers, 2) active population health management to preserve and encourage health on the part of enrollees, coupled with support for key delivery system reforms to ensure efficiency in care delivery, and 3) more selective provider contracting or network design to attack price growth. And, amazingly, competition in the new marketplaces is pushing them to pursue these strategies--an outcome I thought only a public option competitor would finally commit them to pursuing. I was, happily, wrong.

I hope that I'm right that multi-payer competition can work to give consumers what they want while simultaneously muting commercial health premium growth. Because if I'm wrong, Uncle Sam is our last chance.

No comments:

Post a Comment